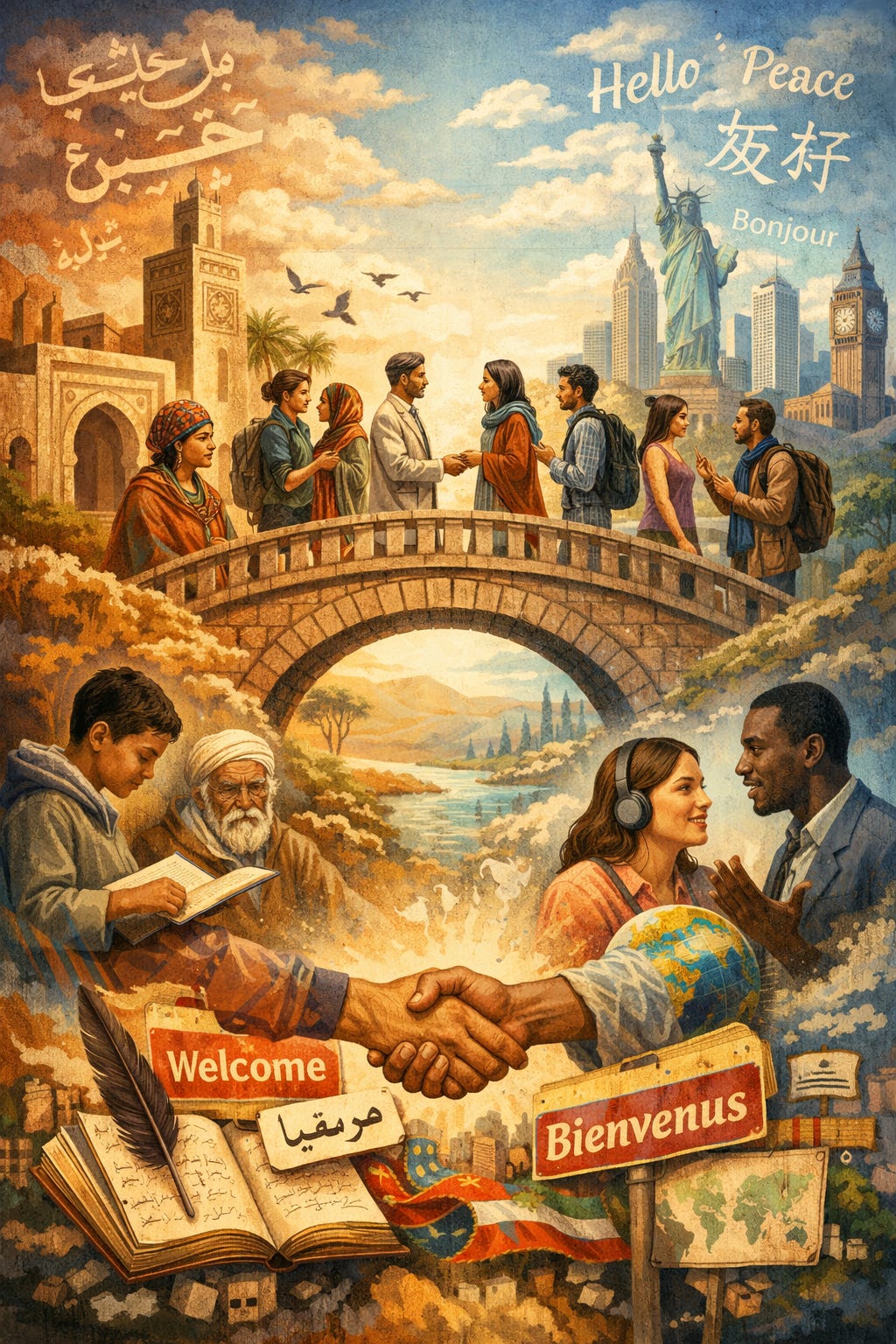

Between Tongues and Horizons: When Language Becomes a Bridge—or a Border

Exploring How Words Connect, Divide, and Shape Our World

Language arrives before intention.

Before belief.

Before even memory.

It settles on our tongues as a home we did not choose, yet one that shapes how we walk through the world.

To speak is never neutral.

Every word carries a history, a geography, a way of seeing. Language can open doors between people—or quietly lock them. It can become a bridge of recognition or a border of misunderstanding. In Morocco, as in the wider world, this tension is not abstract; it is lived daily, breathed into conversations, classrooms, markets, and streets.

Language as a World-Maker

The linguist Edward Sapir once wrote that “language is a guide to social reality.” His student Benjamin Lee Whorf went further, arguing that language does not merely describe the world—it structures how we perceive it. We do not simply speak language; we think through it.

When a Moroccan child grows up navigating Darija at home, Amazigh in the village, Classical Arabic at school, and French or English in professional spaces, they are not just multilingual—they are multivisioned. Each language frames reality differently:

Darija for intimacy and humor

Amazigh for land, ancestry, and memory

Arabic for formality, faith, and abstraction

French and English for mobility, global access, and power

Pierre Bourdieu called this the “linguistic market”—a space where languages are not equal, where some accents carry authority and others are quietly devalued. Language, in this sense, becomes capital. And like all capital, it can include or exclude.

When Language Becomes a Border

A border does not always need fences.

Sometimes it appears in a job interview when a perfect idea stumbles over an imperfect accent.

Sometimes in a classroom where intelligence is mistaken for fluency.

Sometimes in a society where one language is labeled “modern” and another “backward.”

The anthropologist Frantz Fanon, writing from a North African and postcolonial perspective, warned that speaking the language of the colonizer often meant internalizing their worldview. “To speak a language,” he wrote, “is to take on a world.” And sometimes, that world comes with invisible hierarchies.

In Morocco, linguistic borders can separate rural from urban, elite from popular, center from margin. Worldwide, they divide migrants from citizens, the Global South from the Global North. Language becomes a test one must pass to be seen as fully human, fully competent, fully legitimate.

Language as a Bridge in Everyday Interculturality

Yet language also bends.

In the Moroccan souk, languages overlap like woven carpets—Arabic slipping into French, Amazigh grounding the exchange, gestures filling the gaps where words fail. Meaning is negotiated, not imposed. This is interculturality in its most honest form: imperfect, fluid, alive.

Claude Lévi-Strauss believed that cultures do not exist in isolation but in relation. Language is the primary site of that relation. Every act of translation—literal or emotional—is an ethical act. It says: I am willing to meet you halfway.

Across the world, hybrid languages emerge: Spanglish, Hinglish, Arabizi. Purists may resist them, but sociologists see something else—proof that people refuse to let language remain a wall. They turn it into a crossing.

Seeing the World Through Many Words

Language shapes not only what we say, but what we notice.

Some languages name relationships precisely; others name emotions more subtly. Some emphasize action, others state of being. When we learn another language, we do not add vocabulary—we add perspective. We learn that reality is not singular.

As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously wrote, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Multilingual societies, then, live with wider horizons—if they choose to honor them.

Choosing the Bridge

The question is not whether language is a bridge or a border.

It is who controls it, who values which voices, and who is willing to listen.

In Morocco, the future of language is not about choosing one tongue over another. It is about recognizing that dignity speaks in many accents. Globally, intercultural dialogue does not begin with perfect grammar—but with humility.

To learn another language is to accept that your way of seeing is not the only one.

To listen across languages is to practice justice.

To speak with care is to build bridges where borders once stood.

And perhaps that is the quiet power of language:

It can divide the world—

or teach us how to share it.